The Anti-Anti-Americans

/All summer long, Paris was intermittently spectacular and spectacularly intermittent. Even the brightest spectacles came and then, abruptly, went. Every hour on the hour after nightfall, the Eiffel Tower is forced to light up, for exactly ten minutes, in a crazy-quilt pattern of scintillating lights. The lights were put in for the first night of the millennium and taken down the following year, but they were such a hit that they have been permanently reattached to the tower’s girders and are turned on according to a schedule. Charming when it first appeared, the show now has something dutiful and undignified about it, like a society lady in her eighties wearing spandex and shimmying her hips; it’s nice to know she can do it on New Year’s Eve, but you don’t really want to see her doing it every night. Another strange, temporary summer spectacle is the Paris Plage, the absurd and touching brainchild of Bertrand Delanoë, who is the green and gay mayor of Paris. The Plage, an artificial beach that extends along the Right Bank of the Seine, from the Tuileries gardens to just past the Île Saint-Louis, complete with beach shacks, cafés, and strolling musicians, has been particularly welcome in the unequalled heat, which began in July and has lasted through the summer. (A hot day in Paris often ends with a sad cool breeze. These days haven’t.) The French genius for order, however, insured that the thousands of tons of sable that were shipped in by barge to make the Plage possible are neatly packed in linked wooden boxes—making the beach, in the end, the world’s oddest, longest, narrowest sandbox. What is startling is the gravity with which people stretch out in the sandbox and apply sunscreen and lounge in chairs and read books while the tourists walk by. In the early morning, the “bathers” go home.

Continuing the theme, most of the summer’s news was dominated not by Iraqis or Americans but by strikes—by part-time workers in show business, the intermittents du spectacle, as they call themselves. (It sounds just as odd in French as in English.) The history and the grievances of the intermittents du spectacle are hard to summarize, or, for that matter, to believe. Basically, for thirty years or so part-time actors and night-club bouncers and musicians in France have had a ridiculously generous unemployment-insurance deal, which, owing to the “precariousness” of their situation, lets them work for about three months to collect a year’s worth of unemployment insurance. The unemployment fund is a general one, and all workers contribute to it. The people who were paying the intermittents, producers and theatre owners, were perfectly happy to have the plumbers and electricians of France essentially subsidizing the out-of-work actors and actresses. It was understood to be a kind of cultural subvention, a way of keeping the theatre technicians, in particular, from having to leave the business in the long stretches between productions. (It was also a way for the C.G.T., the old French Communist-dominated union, to keep a stranglehold on film and theatre, for practical and, at times, ideological reasons.

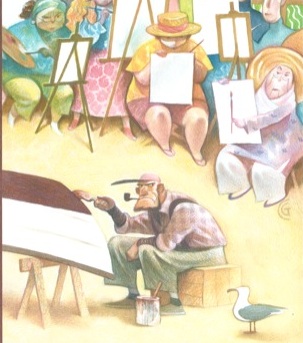

Eventually, though, the other unions rebelled against the arrangement and, this spring, made a more or less surreptitious deal with the bosses to alter it, on the rationale that an excellent remedy for the precariousness of the position of part-time actors already exists: it is called “waiting on tables.” Now the part-time actors would have to work three months out of every ten, for only eight months of benefits. At this, the intermittents went out on strike—a difficult thing to do when you are not working in the first place, but they managed it, holding marches that shut down the center of Paris, throwing bits and pieces of old film into the streets, and displaying sloganeering of a high quality. (One sign claimed to be quoting Marcel Duchamp: “The taste of a time is not the art of the time,” meaning that the waves of budget cutting or keeping should not be allowed to interfere with the sanctity of independent culture.) Then they set to work shutting down the summer music and theatre festivals, one by one—Aix, Avignon, and most of the music at the Paris Plage. (The Rolling Stones, however, were able to go on, for reasons that were not well explained but may have had something to do with E.U. regulations, or with a sensible French fear of Rolling Stone roadies.)

There was a widespread understanding, too, that the inherent theatricality and self-dramatization of French strikes were at last being placed in the hands of those who had been practicing for years for the opportunity to be theatrically self-dramatizing—for the moment when the manner of French striking became the subject of French striking. Even Jean Baudrillard, who turned the paradoxes over and over in his mind in Libération—the society of spectacle had at last produced a striking proletariat of spectacles—didn’t know whether to clap or to shake his head. For many people in France, it produced, surprisingly, a sense of dour hopelessness greater than that caused by any of the other strikes that have happened in France in the last eight years. It is one thing to have your country stopped regularly by truck drivers and railroad engineers; at least this has the savor of blue-collar rectitude. When the country and its joys can be shut down by part-time trombonists, however, something is wrong, or at least ridiculous.

The question of the intermittents was so pressing—omnipresent in the newspapers and on television—that there was little room left for the Americans. With the egocentrism that is our national character (and which we call “innocence” and others “arrogance”), Americans in Paris were full of apprehension about their welcome, only to discover that they were regarded as less worrisome than your son Gilles, the failed actor. Paris Jazz, the commercial classic-jazz station, played its twenty-four hours of Prez and Billie; the Lacanian psychoanalysts in the pages of Le Monde praised Ang Lee for giving us the Oedipal life of the Hulk; the event of the summer was the rerelease of “Wanda,” a film by the forgotten American feminist filmmaker Barbara Loden. The special summer feature in Le Figaro was a happy, undisturbed account of a trip taken on the old Route 66 by a French journalist. (“The gastronomy,” he concluded gravely, “is, frankly speaking, peculiar.”) Nothing remotely like the overtly poisonous anti-French propaganda of the Murdoch media could be found anywhere in Paris. Whatever bad feeling there might be took the form of mordant jokes (butcher to American customer: “Say hello to George for me”) and a certain defensive pride. Even the Foreign Minister, Dominique de Villepin, every day announced how much France likes America, insisting that only Iraq divides us.

A kind of generalized anti-Americanism, not simply opposition to the war in Iraq, does exist, but it has become “a routine of resentment, a passionless Pavlovianism,” rather than a critique of United States policy, as the historian Philippe Roger concluded in “L’Ennemi Américain” (“The American Enemy”), a recently published six-hundred-page tome devoted to the subject. Anti-Americanism, though of course it has life as a muttered feeling, has almost no life as an idea or an argument. Even in its strongest and most overt form, it tends to be Olympian and condescending rather than vituperative.

The most effective and most talked about of the new anti-American texts, Emmanuel Todd’s “Après l’Empire” (“After the Empire”), argues, through a series of analogies to the Roman and Athenian Empires, that America has, slowly in the Clinton years and more vigorously since 9/11, drifted away from a “soft” universalist imperialism of culture and toward a “ hard” military imperialism. This military imperialism, however, is too weak to put on more than “micro-theatrical military displays”—intermittent spectacles—against limp opposition. Resorting to such “Triumphal Arch” imperialism, Todd points out, is always a sign that the empire is finished. (One of his cleverer points is that the trappings of a service economy—lawyers, bards, and attendants—replicate the condition of a Roman imperial household more than that of an industrial community.) Todd’s book is actually rather compassionate. It’s all over, and has been for years. We’re just too dumb to know it.

Far more lucid and arresting, and just as likely to sell books and get attention, are the views of the anti-anti-Americans—that small but loud bunch of philosophers and journalists who share the American conviction that September 11th was an epoch-marking event, and that how open societies react to it will help determine how open they get to remain. Though members of this group can be counted on the fingers of one hand (with room left over for a thumb and a pinkie), they are in a way the most potent of contemporary French thinkers.

There are at least two kinds of anti-anti-Americanism, though the first, represented by Jean-François Revel, the old lion of French liberalism, is simply displaced nationalism. Revel’s new book, “L’Obsession Anti-Américaine” (“The Anti-American Obsession”)—which was a No. 1 best-seller in France for a month last fall—is a defense of the American nation so enthusiastic that it would embarrass George Washington’s mom. More interesting—for an American reader and observer, at least—are those thinkers who, because they have to defend American behavior without being in any way American nationalists, are forced to define a new kind of international liberalism.

“Anti-Americanism in France is always a magnet for the worst,” Bernard-Henri Lévy said one evening in July. He was sitting in the study of his apartment on the leafy Boulevard Saint-Germain, and even for a casual meeting he wore, as he has done in public for thirty years, an elegant uniform of black suit and open white shirt, the collar lapping over his lapels. B.H.L., as everyone calls him, who remains one of the central media figures in France, has had a great critical success with a book entitled “Qui A Tué Daniel Pearl?” (“Who Killed Daniel Pearl?”), which is, in a way, the most vivid and intensely realized of all the “pro-American” texts. It is an inquiry into the kidnapping and murder in Pakistan last year of the Wall Street Journal reporter, and will be published next month in English by Melville House Books. Unapologetically personal, the book recounts B.H.L.’s own investigation in Pakistan and India, and also in America, with sidelights on his previous campaigns in Bosnia and Bangladesh. One reason for its success in France is that it is written almost in the tone of what the French call a polar, a noirish police thriller, full of one-sentence paragraphs and portentous cliff-hangers (“He was the man who knew too much. But what did he know?”). It also attempts, on a deeper level, to paint a character portrait of the man who did kill Danny Pearl, or, at least, arranged his kidnapping: Omar Sheikh, the Islamist who was convicted in Pakistan last year. Like Mohammed Atta, he turns out to be not a barefoot wild-eyed Mahdi but a child of the West, London-raised and educated—the New Naipaulian Man, lost between two cultures, enraged at the West and mesmerized by a fantasy of Islam, only now armed with a total ideology and an A-bomb.

On a third level, “Who Killed Daniel Pearl?” is a demonstration piece, a deliberate embrace by a French intellectual of an American journalist, and a book that insists that the death of an American journalist (and one who worked for the Wall Street Journal, at that) was as important for France as for America. B.H.L.’s purely political, or forensic, conclusion is that it is naïve to speak of Al Qaeda as an independent terrorist organization. At most a band of Yemenis and Saudis, the Al Qaeda of American imagination and fears—the octopus of terrorism capable of bringing tall buildings down in a single morning—is largely controlled by the Pakistani secret service, he says, and he concludes that Pearl was kidnapped and murdered with its knowledge. Pearl was killed, B.H.L. believes, because he had come to understand too much about all of this, and particularly about “the great taboo”: that the Pakistani atomic bomb was built and is controlled by radical Islamists who intend to use it someday. (He writes that Sheikh Mubarak Gilani, the cleric whom Pearl had set out to interview when he was kidnapped, far from being a minor figure, is one of Osama bin Laden’s mentors and tutors and has a network in place in the United States. John Allen Muhammad, the Washington sniper, Lévy claims, in a detail that, if not unknown, is unpublicized in the United States, had transferred from the Nation of Islam to Gilani’s sect shortly before he began his killing spree.)

The essential conclusion of this central Parisian thinker and writer is, therefore, not that the American government ought to be more conciliatory toward the Islamic fundamentalists but that our analysis of the situation and its risks is not nearly radical enough. “I am strongly anti-anti-American, but I opposed the war in Iraq, because of what I’d seen in Pakistan,” Lévy said. “Iraq was a false target, a mistaken target. Saddam, yes, is a terrible butcher, and we can only be glad that he is gone. But he is a twentieth-century butcher—an old-fashioned secular tyrant, who made an easy but irrelevant target. His boasting about having weapons of mass destruction and then being unable to really build them or keep them is typical—he’s just a gangster, who lived by fear and for money. Saddam has almost nothing to do with the real threat. We were attacking an Iraq that was already largely disarmed. Meanwhile, in some Pakistani bazaar someone, as we speak, is trading a Russian miniaturized nuclear weapon.”

The relentless first-person address of Lévy’s new book has been mocked—“Tin-Tin in Pakistan”—but its egocentrism feels earned, and even admirable. There are three kinds of writers addicted to the first person: the kind whose “I” remains a pillar of self-reliance, supporting the text (Camus and Bruce Chatwin are both masters of this sort); the kind whose “I”s magically become “you”s (Montaigne, Thurber); and then a third, rarer kind (Mailer, Malraux), whose insistent “I”s somehow become an extended and inclusive “we,” and who, through sheer lack of embarrassment about their own self-dramatization, end up enacting the dream life of their generation. B.H.L. is, or has become, in his last three books, a writer of that kind, and of that stature.

“The real issue, which the Americans don’t see, is that the Arab Islamist threat is partly manageable,” he went on. “One can see solutions, if not easy ones, to the Israeli-Palestinian question, to the Saudi problem. The Asian Islamist threat, though, is of an entirely different dimension. There are far more people, they are far more desperate, and they have a tradition of national action. And they have a bomb. Even North Korea is less dangerous than Pakistan—a Stalinist country with a defunct ideology and a bomb is infinitely less dangerous than a country with a bomb and a new ideology in the full vigor of its first birth. That is the real nexus of the terrorism, and fussing in the desert doesn’t even begin to address it.

“The French opposition to the war was opportunist in part, rational in part, but mostly rooted in a desire not to know. What dominates France is not the presence of some anti-Americanism but an enormous absence—the absence of any belief aside from a handful of corporatist reflexes. This whole business with the intermittents is typical: it’s corporatism pursued to the point of professional suicide. All that we have to replace it with is the idea of Europe; so far, we have overcome romantic nationalism, but we have nothing left to replace it with.”

Even the most resolutely anti-anti-Americans in Paris don’t know what to do about George W. Bush—no one since Joseph McCarthy has been such a gift to anti-Americanism in Europe, and particularly in France. Even the unprecedented heat that has swept Europe is provocative, people feeling that a warming so global might have something to do with global warming. The centrist journal Le Débat, in an editorial defending the American intervention in Iraq and criticizing the French government for opposing it, felt compelled to call the current Administration “perhaps the worst in American history.” What the French, from left to right, see as Bush’s shallow belligerence, his incuriosity, his contempt for culture or even the idea of difference—no one in France can forget his ridiculing an American reporter, on his one visit to Paris, for daring to speak to the French President in French—make him a heavy burden even for the most wholeheartedly pro-American thinker.

“No completely defensible cause has ever been so poorly defended as this one,” André Glucksmann said in his apartment, up in the Tenth Arrondissement, the day after Bastille Day. He was speaking of the case made for the war in Iraq. “The great mistake was to settle for the absurd argument about weapons of mass destruction. Had the appeal for war been made on straightforward humanitarian grounds—the case against Saddam, this guy is a killer, we can do something about him and we must—I know it would have worked in France. Look, Bernard Kouchner”—the co-founder of the humanitarian group Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders)—“is the most popular political figure in France, beyond question, and the moment the war was broached he came out in support of it, on purely humanitarian grounds. He lost perhaps one per cent in the polls. The French think, Well, arms, everyone has arms, and the French élite knew the kind of thug and gangster that Saddam was—they had contempt for him—and they communicated that. But people really did learn something from Bosnia, and had the case been made resolutely that we had another Milosevic it would have worked.”

Glucksmann grimaced as he spoke, and then the grimace turned into a smile—of resignation, understanding, attempted forgiveness. It was the day after the French state routinely makes itself look foolish by parading new guns and old uniforms up and down the Champs-Élysées, and then makes itself look beautiful by setting off violet and gold fireworks outside the Eiffel Tower for an hour that same night. In the middle of the relentless heat wave, Glucksmann struggled to keep his cool and his good humor. On the page, he is relentlessly sardonic, and even sarcastic, but in person he bends toward bemusement. His long gray hair and strong, rather Russian-seeming face give him a bearing and intensity that one associates more with Eastern European intellectuals than with his suave and ironic countrymen. At sixty-five, he remains an original. Beginning in 1968 as an anarcho-Maoist, and as an ally of Sartre in the founding of Libération, he has made an exceptional journey, to end in a place that belongs to no one but him. Though he is staunchly pro-war (and comes as close to being pro-Bush as any Frenchman can, announcing that “underneath the carapace of the Baptist bigot there is someone who is a nearly Shakespearean figure, a man who has met tragedy and recognized it as such”), he is not really of the right. He is simply pessimistic.

Glucksmann believes that the only worthwhile “political” project is the constant, unrelenting, and most probably futile amelioration of obvious suffering. “It’s very odd that the idea of the doctor, and of medicine, predates by thousands of years the actual ability of doctors to help anyone in more than small ways. Why should it be?” he said once in a conversation. “Well, it’s because we recognize the presence of evil as being stronger than the promise of a cure. The simple Hippocratic oath, ‘First, do no harm,’ is a far, far more radical sentence in the history of thought than it seems. It recognizes the existence of evil—illness—that is in many ways beyond our control. It is the opposite of magical thinking, witch-doctor think, which promises to make well, to cure. ‘Do no harm’ is the truly radical sentence; ‘Cultivate your garden’ the unforgivable one.”

Above all, literature is for him the natural model of thought: he sees history through the lens of Chekhov and Dostoyevsky and Aristophanes. In the nearly two years since September 11th, Glucksmann has written two books, neither of which has yet been translated into English. The first, “Dostoyevsky in Manhattan,” is a strange, brilliant, nightmarish rumination, which sees in the attacks not some strategic rebound or medieval throwback but the evidence of a basic and essentially irrational will to destruction that has found a new home in the Islamic world. To explain the attacks with reference to a “cause”—poverty, or the Palestine question, or Islamic eclipse—is to miss their essential nature as surely as would reducing the Holocaust to flaws in the Treaty of Versailles. The second book, “West vs. West,” which he has just finished, is an acerbic, unhappy account of the Franco-American quarrels, rich in a kind of head-shaking disbelief at the unreality of both sides, but especially the French bien-pensant one. Both books point to the same moral. Mass killing has become, in our time, the means of expiating doubt and uncertainty, and the central reality of September 11th was that “a capacity for massive destruction, until then available only to a few, was suddenly in every hand, in countless pockets, and in millions of deranged minds.” Dostoyevskian killers were descending on Chekhovian cities.

“What’s happening is simple,” Glucksmann said. “There are no longer battles, or Auschwitzes. But anyplace can become an Auschwitz. ‘I kill, therefore I am’ is the motto of the new generation of murderers. It’s really very easy: the Hutus attacked with machetes and a few machine guns, and committed a genocide of a million people. The Russian Army blunders its way into Grozny, and no one cares or objects. Rwanda and Chechnya are the intimations of Manhattan—they are rooted in a will to kill no matter whom. The crime is to be,and the act is to kill: to be a Manhattanite on that morning was your crime, as to be a Jew was the crime in Germany.

“In France, the problem, more than a will against America, is a will to hide—to hope not to be seen at all. But it is insane for the French to see all this as somehow apart from them. It began against us. Nine years ago, the G.I.A.”—the Algerian Islamists—“who are a group of the same kind, hijacked a plane and were going to fly it into the Eiffel Tower! The only difference? They didn’t know how to fly a plane! They were trying to use the pilots to do their work. Seven years later, they knew how. So to imagine that we are somehow immune is not only crazy on principle—it is the direct opposite of what we know to be the facts!”

He shook his head. “There is a kind of nihilism at large in the world now, which ranges from the murderous nihilism of the terrorists to the comic, domestic nihilism of the intermittents, who have only the power to block, to destroy, and they use it.”

What is finally moving about the anti-anti-Americans in France is that they are defending a cosmopolitan tradition—the tradition of the Marshall Plan and the melting pot, where, as B.H.L. rhapsodizes, Daniel Pearl could be Jew and journalist and American and internationalist all at once—that they continue to identify, stubbornly and, these days, perhaps quixotically, with the United States. What is striking, and a little scary, in Paris this year is the absence of anti-Americanism—of a lucid, coherent, tightly argued alternative to American unilateralism that is neither emptily rhetorical nor mere daydreaming. (In fact, it is easier to find this kind of argument in Britain than in France.) The real threat to France is not anti-Americanism, which might at least have the dignity of an argument, an idea, and could at least provoke a grownup response, but what the writer Philippe Sollers has called the creeping “moldiness” of French life—the will to defiantly turn the country back into an enclosed provincial culture. “For the first time, French people care about their houses,” a leading French journalist complains in shock. “That was always a little England thing—and now you find intelligent Parisians talking all the time about home improvements.” This narrowing of expectations and horizons is evident already in the French enthusiasm for cartoon versions of French life, as in “Amélie,” of a kind the French would once have thought fit only for tourists. It has a name, “the Venetian alternative”—meaning a readiness to turn one’s back on history and retreat into a perfect simulacrum of the past, not to reject modernity but to pretend it isn’t happening.

This urge could be felt in an almost unconscious force deforming even the two major exhibitions of the summer, the Centre Pompidou’s Jacques-Henri Lartigue retrospective and the National Library’s show of the complete Cartier-Bresson, in which the two great photographers were suddenly made cozy and diminutive. The Museum of Modern Art’s outsize 1963 black-and-white prints of Lartigue’s photographs of speed and action were put on view in an anteroom only to be debunked inside, with all the albums and stereoscopes from which the great work was adapted put on view in “period” glass cases. See, the show said, he’s a little Frenchman, one of us, small and stylish and delectable and amateur. The refusal to live in the world as it exists is a kind of nihilism, too. It is possible to look into Lartigue’s work and see a modern visionary of dynamism and forward motion; possible, too, to make him a static and comfy mediocre artist of domesticity. It depends, perhaps, on just how spectacular you want things to be, and for just how long. ♦