Fear and Torture

/The tragic resonance, in the global war on terror, of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s report on torture, released yesterday, will not, and probably should not, fade any time soon. It reveals that Americans engaged in acts, on behalf of and with the approval of and under the direction of their highest elected leaders, that, when performed by others elsewhere, we have not only condemned but actually treated as capital crimes. There is no turning back from such knowledge.

The excuses are many and are sure to proliferate, as will the defensive tone and the apologetics—and, not without some reason, some call for understanding. The defenses are of two kinds, both as false as they are deeply felt. First, there is the truth that the C.I.A. interrogators were, for the most part, following orders and doing what they had been told they were authorized to do; to make them the prime villains is to clear the democratically elected politicians who allowed this to happen—and, more important, to clear the democracy that elected those politicians. We are all implicated, not just those who drowned and froze and tormented prisoners. If blame is to be had, it must not move only upward, to the bosses; it must move outward, to those who chose the top men and to the many who explicitly endorsed their reading of the “war on terror” and the threat of terrorism. (That prospect, one would guess, was at the heart of President Obama’s reluctance to release the report in the first place; to blame no one might be unacceptable, but to blame anyone in particular was to blame everyone.)

Second, and running directly from the general responsibility, there is the claim that if we hadn’t tortured people—hanging them upside down, raping them rectally, and all the horrible rest—some terrorist would have been able to kill more Americans, possibly with a radioactive bomb, or worse. This is an empirical claim, but without much of an empirical foundation: the report insists, for instance, that the famous “courier,” a key in the search for Osama bin Laden, was discovered (and certainly discoverable) not through torture at all but through normal investigative means. But it is also a moral claim of exceptionalism: after all, every nation can argue that it needs to torture prisoners in order to protect its people. The North Vietnamese were under far more direct threat from American bombers than Americans have ever been from mostly remote Arab terrorists, yet no one would ever suggest that the Vietnamese were justified in torturing American pilots, even if they could have found out about, say, the targeting and timing of bombing raids, which might conceivably have saved Vietnamese lives. That was, we said, and would say again, no excuse. We have none, either. This is a good place to make it clear that, in this case, comparisons to Nazi and Communist tortures, far from being some kind of wild violation of decorum, are exactly what’s essential—essential because without the belief that, even in wartime, there are acceptable and unacceptable forms of violence, the post-Second World War war-crimes trials, in which we place great pride, would indeed be no more than what the ex-Nazis always said they were: pure victor’s justice. If we believe, as we do, that those trials were truly just, then that is because the acts that they sanctioned, including the torture of prisoners, were evil inherently, not just evil when done by other folks.

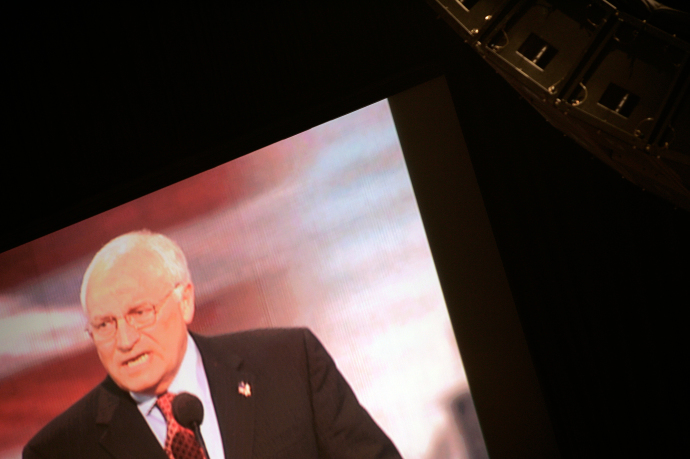

Searching for ultimate responsibility, we look at individuals: at Dick Cheney, clearly engaged and still unrepentant, and at former President George W. Bush, whom the report reveals to have given formal permission for the torture but to have been unaware of its extent until 2005—a portrait of a disengaged and incompetent chief executive that will shock even his not easily shocked detractors. But we need to look also at ourselves. We need to look at the climate of fear that all but a few created and participated in after 9/11. That climate of fear made the imminent threat of more and worse terror attacks seem plausible, even highly likely. It was, in part, the natural and inevitable consequence of an atrocity that took so many lives so quickly and so unexpectedly. If that could happen, what couldn’t? But it was also engineered, crafted, and engaged in by many who knew better, or should have. When Dick Cheney and the rest chose to cower in bunkers instead of, say, leading Wall Street workers across the bridges and back to work, unafraid; when polemicists and editorialists spoke the language of revenge and reprisal instead of the wiser language of recovery and resilience; when the thick cloud of fear was not dispelled by increased understanding but held in place by panic—when all of these things happened, the move toward the violation of all the norms of decency was almost certain to follow. Our collective fear made bad things happen that we can now hardly believe took place. “Be not afraid!” a wise man said, seven times, summing up his lesson. It is even deeper wisdom than we knew.